- Home

- Bobbie Pyron

The Dogs of Winter Page 11

The Dogs of Winter Read online

Page 11

The Christian Lady would smile and take my bowl. “What a good boy you are, so polite.”

I smiled.

“What’s your name?” the Christian Lady would ask.

And always I would reply, “My name is Dog Boy.”

One time as I sat with the dogs atop a heap of concrete and bricks eating a piece of bread, I thought I spotted the dark hair and loose legs of Pasha.

I leapt to my feet and scrambled to the ground. “Pasha!” I cried, pulling on the arm of the dark-haired boy waiting for a bowl of soup.

The boy turned his head and looked down at me. The eyes were dark like Pasha’s and tilted up at the corners, like Pasha’s.

“It’s me,” I said, plucking at his sleeve. “Remember? Leningradsky Station?”

But although the eyes may have been Pasha’s, what lived behind them was not. Because the place behind the eyes was dead. Behind the eyes lived only a ghost.

My first winter with the pack passed in this way. The trains rocked me to sleep, and the trains showed me the world. And always, the dogs loved and protected me.

I no longer looked for a red coat. I knew I would never see her again.

Now when I read the stories from the few torn pages of my book of fairy tales, I heard only my voice — the voice of Sobachonok — not the sound of my mother’s voice. The dogs lay close to me as I read to them of witches and snow queens and the magic firebird. Grandmother’s white head rested on my knee, Rip sprawled half on and half off my lap, and Little Mother, Lucky, and the puppies lay close by. Smoke dozed always a little apart from the rest, watchful, even in sleep, for trouble.

On through the night, and the months, and the winter we traveled with the train, until one day it was spring.

The hand of The City opened.

Once again, shopkeepers stood outside their storefronts talking and smoking. Once again the wooden stalls outside the train stations filled with people selling everything: food, drink, newspapers, books, cheap wooden dolls nesting one inside the other, shiny metal replicas of St. Basil’s church, boxes of cigarettes.

The people coming and going in the train stations and on the sidewalks slowed long enough to drop coins in this boy’s outstretched hand. And when I said, “Spasibo,” they sometimes smiled.

Once again, workers in office buildings took their lunch to the plazas and the parks. They turned their faces to the sun and closed their eyes.

This brought a new trick from Lucky. He stole. The first time I saw him do this was on a warm day. The trees in the small plaza were tipped with the youngest of green. The snow was all but gone, leaving behind many interesting things in the small piles of trash. I was searching with great interest through one of these piles when the corner of my eye caught sight of Lucky. He crept on his belly up behind a man with his paste-white face turned up to the glorious sun and his eyes closed in contentment. At his feet a brown bag of lunch waited to be eaten.

Slowly, slowly Lucky crept toward the bag. I held my breath as he stretched his neck as far as it would go. He snatched the bag with great tenderness. Slowly, quietly backward he crept with the bag while the man continued to worship the sun. When Lucky and the bag were clear of the man, he trotted over to us, head and bag held high, tail wagging. He dropped the bag at my feet.

“Lucky,” I scolded. “We do not steal.” I said this even as I unfolded the top of the bag.

We moved out of sight of the man — still enjoying the sun — and I divided up the contents of the bag. I scratched Lucky’s ear. “I’m not mad at you. Your mother didn’t tell you it’s wrong to steal.”

I gasped. There, at the bottom of the bag, glowing like the sun setting in the winter sky, was an orange.

I held the orange under my nose and drank in the wonderful smell of its orangeness. “Oh, he must be a very rich man,” I said to the dogs. They sniffed the orange and turned back to their bread. I smiled. The orange would be just for me. I had eaten an orange only once or twice in my life. This one, I would make last for many days.

I was no longer content to ride the trains, and neither were the dogs. Smoke disappeared for longer and longer periods of time, as he had before. Grandmother spent long hours on the sun-warmed sidewalks, sleeping. Little Mother did her best to keep track of the puppies, whose long legs carried them farther than she liked. Lucky and Rip made new friends of all the dogs on the streets after the long winter.

And like the dogs who lived on the streets, with each passing day, more and more homeless children emerged from wherever they had been during that winter. They emerged pale and thin and hungry for whatever they had not had.

As the days grew longer, packs of older children roamed the streets looking for those made weak by the long winter. I watched a pack of younger children steal the shoes and coat and hat from another child sleeping in a doorway. I watched a snarling pack of older boys torment a drunken man cowering in a bus shelter. It was not enough for them to steal what little money he had and to steal his bottle of vodka; they also taunted him.

“You crazy pig!” they cried. One boy knocked the drunkard in the head with a stick. “You stupid fool,” another boy sneered. He kicked the drunken man in the seat of his pants as the man tried to stumble away from the pack of boys. The man fell to his knees. The boys descended on him like vultures.

Grandmother and Rip pressed against my knees and whimpered. We turned and walked away from the cruel, cruel laughter of the boys. I rubbed my thumb over and over the edges of the tooth in my pocket.

“I don’t know why humans act the way they do,” I said that night to the dogs. We were all curled together in the warmth of the basement beneath an abandoned, crumbling church. Little Mother had found this place and brought us here.

“Sometimes they are cold and heartless like the Snow Queen. Sometimes they are full of ugliness and hunger like Baba Yaga.”

Little Mother scrubbed my hand with her tongue, one paw pinning the hand to the ground. I pulled a small bug from my hair, no bigger than a grain of rice. I crushed it between my fingers. “Too many are like the Little Match Girl — lonely and starving.”

Lucky rolled onto his back, waiting for a scratch. “Ah, Lucky, my thief,” I said with a smile. “Why should I scratch your belly when you steal?”

He had a new trick to steal food. He picked one particular person from the crowd leaving the food stalls with their lunch packet. He followed them a short distance across the stone square. Then he would let out a loud woof. The lunch packet would fall to the ground from the startled person and, before the person even knew what had happened, Lucky snatched up the food and ran. Sometimes he shared with us, and sometimes he did not.

Mostly he shared. I scratched his belly.

The rains of spring came and with them, hunger. People no longer ate their lunch in the squares and parks. The rain and wind pushed the people too quickly down the sidewalks to stop and give a small begging boy a few coins so he could eat. I retreated to the metro stations, where it was always daytime and dry, and the people coming and going to and from the trains were not in such a hurry to go out in the world. Coins clinked in my hand, and bread and sausages filled our bellies.

But, of course, soon rain also drove the children from the streets and the doorways and their homes of cardboard to the world below. They begged, they stole, they fought, and they formed their own packs for protection against the gangs of older boys and against the militsiya.

And as always, the dogs and I watched from the shadows and from the corners and from behind gleaming statues of brave men.

It was on one of these rain-filled days in the Kitay-Gorod metro station that I heard a familiar voice as I rooted through an overflowing garbage bin. “That little cockroach is barely big enough to do his work.”

I turned around and looked into the silver-gray eyes of Rudy. There he stood, squinting at me through a cloud of smoke, cigarette dangling from his lip. He still wore the tattered policeman’s jacket and the skinny black pants. His face

looked thinner. A dark bruise sprawled the length of his jaw.

The smallest finger of warmth touched his ice-cold eyes. “Well, look who we have here. It’s the little circus mouse.”

I wiped my hands on my pants. “Hi, Rudy.”

He looked me up and down as he walked around me in a slow circle. “What dead bum did you steal those clothes from?”

“I got them from the Christian Ladies,” I said.

“Ah,” he said, flicking his cigarette onto the floor and crushing it beneath the heel of his boot. “God bless the Christian Ladies. They fill your belly and steal your soul.”

“Where’s Tanya?” I asked, looking past him. Rarely was there a Rudy without a Tanya.

He ran a dirty hand through his hair. “Gone. She is gone.”

A chill ran through me. I had heard those words before.

“Is she dead?” I asked, rubbing the tooth in my pocket. Yes, there had been a scream, there had been a sticky, red spot on the floor that no amount of scrubbing could —

“She might as well be,” Rudy said, his voice heavy and soft. “They took her away to an orphanage somewhere outside the city.”

Rudy stared at the pictures made of tiny square tiles on the walls. “I tried to find her, you know. I asked around, even took a bus to a place I heard about north of the city, but …”

“Perhaps she will come back, now that it is spring,” I said. “And she’ll have new clothes and she’ll have had good food to eat, and —”

A slap to my face sent me stumbling backward against the garbage can.

“Stupid kid,” Rudy growled. “Don’t you know anything?” He grabbed me by my coat and shook me.

“The orphanages are surrounded by fences that will cut you to pieces if you try to get in or out. They work you like a dog and beat you and feed you next to nothing. The orphanages eat you alive.”

I gasped. “Like Baba Yaga.”

Rudy raised his hand. I backed away to avoid another slap.

But instead, he ran his hand over his bruised face. “Yeah, kid, like Baba Yaga.”

It made me sad to think of kind Tanya trapped in the witch’s house surrounded by a fence made of bones and grinning skulls.

Rudy put his face back together in a cold, hard mask. “Anyway, she is gone and you should be too.”

“Why?” I asked.

“You need to get far away, kid. You need to get out of the train stations.”

“Why?”

He grabbed me again and shook me. “Because I said so, that’s why. Isn’t that enough?”

I shook my head.

He pushed his face close to mine. His breath was like fire and smoke. “Listen to me,” he hissed. “The gangs are taking over the streets and the metros. They will crush little cockroaches like you beneath their boots. Do you understand?”

I tried to swallow beneath his clenched fist. “But the dogs will protect me.”

Rudy glanced at old Grandmother sleeping in the corner, the puppies curled against her belly. “I will only tell you this once: Get. Out. If I see you again, I won’t know you.”

Rudy and I stared at each other for a long moment. “What about Pasha and Yula?” I whispered.

“Yula is dead,” Rudy said. “And Pasha is a ghost.”

“But —”

A high whistle echoed from the metro entrance. A voice called out, “Hey, Rudy!”

Rudy’s head jerked up, his face went white then red. Three tall boys draped in chains and black, their hair spiked like iron teeth, sauntered toward us. Crow Boys.

Rudy shoved me hard to the floor. “I told you, get out of our train station, you little cockroach!”

The boys in black were getting closer. I could hear them laughing and spitting.

Rudy grabbed my hand and jerked me to my feet, pressing something into the palm of my hand. In a low voice he hissed, “Run.” Then he yelled, “You and those stupid dogs get the hell out of here.”

I woke the puppies and Grandmother and ran as fast as I could down the long hallway, with Grandmother panting at my heels. As we raced up the stairs, I heard laughter and a voice calling, “Run, cockroach, run!”

We ran all the way to the small park with the duck pond where Little Mother and Rip liked to hunt. They raced over to greet us. Little Mother sniffed the puppies from nose to tail; Rip yipped and licked my face as I stood panting, my heart banging in my chest. Rip nudged the fingers of my closed fist. I opened my hand, the hand Rudy had pressed something into. A wad of damp rubles unfolded in my palm.

Poor Grandmother limped to my side and lay down with a groan. Her back legs quivered.

“We’ll rest here,” I said to the dogs, “and wait for Lucky and Smoke. I’ll get us some food thanks to Rudy. Then we’ll go back to the church basement. We’ll be safe there.”

Days of rain passed in the damp dark, below the broken-down church Little Mother had found for us the week before. Grandmother coughed and shivered. The puppies cried and squabbled. They pestered Little Mother endlessly to nurse, even though they were too big for that now. The rain and the damp dark made her forget she was their mother, because she snapped and snarled and, finally, stalked out into the rain. When the puppies tried to follow, she rounded on them viciously. They ran back to me, their tails tucked between trembling legs.

“She’ll be back,” I said as I stroked them. But would she?

Then one day, when I didn’t think any of us could bear the rain and the dark any longer, the sun came out. We woke to wide bars of light striping the muddy floor. We woke to the sound of birds rather than rain.

Someone woofed at the entrance of our den. Lucky bounded down the heaps of rubble, wagging his tail.

Woof!

What could we do but follow him up into the sun?

We squinted against the first strong light in many days. The air smelled alive and green.

Rip and Lucky dashed back and forth, chasing each other through the shimmering puddles. Little Mother wagged her tail for the first time in weeks and allowed the puppies to nip her delicate feet. Grandmother found a sunny dry spot and stretched long in the warmth. Even the ever-serious Smoke joined in a game of chase. We ran, the dogs and I, in widening circles through the bare bones of the crumbling church. We ran and ran through the weeded lot rambling next to the old building. Bits of colored glass glittered in the sun. “You can’t catch me!” I called to Lucky. “You can’t catch me now!”

Suddenly, the toe of my boot caught on something. I rose into the air. My arms and legs spun like pinwheels. I landed with a thud on my back.

Rip and Lucky rushed to my side and licked my face and hands. “I’m okay,” I said, sitting up. Smoke pawed at something beneath the wet weeds and leaves.

I crawled over to him. “What are you looking for?”

Smoke pawed a mat of leaves and sticks aside. A tiny gray face stared up at us.

“Oh!” Smoke and I jumped back. Then we inched forward to get a better look.

I touched the face. It was hard and cold. I brushed the rest of the mat away. A stone slab slumped into the wet ground. The still face stared out from the middle of the slab. I traced the words carved into the stone with my finger. “I can’t read most of this,” I said to Smoke and Lucky and Rip, who were gathered at my side, staring and sniffing at the discovery.

I touched one word. “‘Loved,’ it says.” I touched another word. “This one says ‘death.’” I ran a finger along a trail beneath the stone face. “These are dates. I think they are 1932 and 1975.” Heaviness settled in my stomach. Babushka Ina. She too had a stone slab with her dates on it. It had cost every ruble my mother had.

I stood and looked around. Stone markers of all sizes surrounded us. Some were only humps beneath the moldering leaves; others rose above the matted earth, furred by moss and lichen.

“This is a cemetery,” I said to the dogs. “It’s a place where dead people live.”

We wandered through the rows of markers. On the top of one sl

ept a stone lamb, its head resting on tiny white hooves, its eyes closed and peaceful. On another, crossed swords were carved into stone. I pointed to one word. “Brave.” I pointed to another. “War.” A cloud passed across the sun. I shivered in my damp clothes. “This place makes me sad,” I said. “Let’s go back.”

We did not return to the cemetery again.

A rumble and a crash woke us a few days later. The earth shook like a great beast, waking. Dirt and wood and bricks shook loose. The floor of the church above rained down upon us.

The dogs and I scrambled away from our sleeping corner just as a wooden beam crashed to the ground. “What is happening?” I cried. “Is the world ending?”

A terrible shriek. I looked behind me and gasped. Grandmother lay trapped beneath the fallen beam!

I ran to her side. Blood trickled from her mouth. Her faded eyes searched mine. I stroked her silvered head. “Don’t worry, my babushka. I’ll get you out.” She tried to thump her tail, but it would not lift.

Something screeched above us like the voice of a dragon. The earth moaned and shook again. Dirt and rubble fell upon us. Great iron teeth and claws ripped through the dirt roof above us. I threw my body across Grandmother’s head and shoulders.

Smoke barked a sharp command. He stood at the pile of rubble leading to our door above. The opening was smaller, had become filled with crumbling bricks and dirt. Little Mother pushed her puppies out ahead of her, and then squirmed behind them. Rip frantically dug his way after her. Lucky must already be out, I realized.

Smoke barked again, this time frantic.

“I can’t leave her!” I cried.

He raced to me and yanked on my sleeve.

I pushed him away. “No!”

He grabbed my arm and pulled hard, ripping the sleeve of my shirt. I tumbled away from Grandmother. The earth shuddered. A fine curtain of dust fell across Grandmother. I crouched beside her head and wiped the dirt from her eyes.

Her eyes did not search my face. Her eyes did not smile as they had so many times.

Stay

Stay A Dog's Way Home

A Dog's Way Home The Dogs of Winter

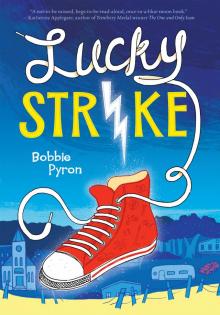

The Dogs of Winter Lucky Strike

Lucky Strike A Pup Called Trouble

A Pup Called Trouble