- Home

- Bobbie Pyron

The Dogs of Winter

The Dogs of Winter Read online

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Part One

Chapter 1: Dreams

Chapter 2: Before

Chapter 3: After

Chapter 4: The Button

Chapter 5: The City

Chapter 6: The Tribe

Chapter 7: Pretend

Chapter 8: School

Chapter 9: The Puppy

Chapter 10: The Mirror

Chapter 11: Ruza

Chapter 12: Rain

Chapter 13: Lucky

Chapter 14: The Pack

Chapter 15: Sweep

Chapter 16: The Dark

Chapter 17: Smoke

Chapter 18: The World

Chapter 19: The Glass House

Chapter 20: Winter

Chapter 21: The Hat

Chapter 22: Dog Boy

Chapter 23: Fire and Ice

Chapter 24: Vadim

Chapter 25: Sister of Mercy

Chapter 26: Betrayal

Chapter 27: The Cold

Chapter 28: The Gangs

Chapter 29: The Trains

Chapter 30: Spring

Chapter 31: Buried Alive

Chapter 32: Garbage Mountain

Chapter 33: The Woods

Chapter 34: Hunting

Chapter 35: House of Bones

Chapter 36: Intruders

Chapter 37: The Biggest Pig in All of Russia

Part Two

Chapter 38: Malchik

Chapter 39: The Return of Rudy

Chapter 40: Broken

Chapter 41: Home

Chapter 42: Trees

Chapter 43: The Woman in the Hat

Chapter 44: Mowgli

Chapter 45: Drawing Tales

Chapter 46: Wild Child

Chapter 47: Hunted

Chapter 48: Fleas on the Dog

Chapter 49: Little Mother

Chapter 50: Reutov

Chapter 51: Fever Dreams

Chapter 52: Away

Chapter 53: Now

Author’s Note

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

I dream of dogs. I dream of warm, soft backs pressed against mine, their deep musky smell a comfort on long, bitter nights. I dream of wet tongues, flashing teeth, warm noses, and knowing eyes, watching. Always watching.

Sometimes I dream we are running, the dogs and I, through empty streets and deserted parks. We run for the joy and freedom in it, never tiring, never hungry. And then, great wings unfold from their backs, spreading wide and lifting the dogs above me. I cry out, begging them to come back, to take pity on this earthbound boy.

It has been many years since I lived with the dogs, but still I dream. I do not dream of the long winter nights on the streets of Russia; seldom do I dream of the things that drove me from my home. My dreams begin and end with the dogs.

Before he came, I watched my beautiful mother.

I watched her at the kitchen sink, her pale hands dipping in and out of steaming water as she washed the dishes, humming.

I watched her hang sheets from the line on the tiny balcony of our apartment, clothespins clamped between her teeth. I handed her more clothespins, two by two.

“Such a good helper, my Mishka, my little bear,” she always said.

Before, I sat in my grandmother, Babushka Ina’s, lap, and listened as she sang the old songs. She rocked me back and forth, back and forth.

Every morning Babushka Ina walked me down the hill to my school. My mother had to get to her job at the bakery long before the sun rose. At school, I sat at the wooden table and practiced my letters. I learned to sound out “cat” and “rat” and to not watch the birds out the windows.

In the afternoon, my mother and I walked back up the long, low hill to our apartment. Babushka Ina cooked my favorite cabbage soup while I practiced my letters and listened to my mother hum.

Before, it was Babushka Ina who slept with my mother at night. I had my special bed in the sitting room. My mother read to me every night from my book of fairy tales.

This is the way it had always been: me and my mother and my Babushka Ina. This was the way I thought the world would always be.

One warm spring day, my mother waited for me outside the schoolyard. Her eyes and nose were red.

She dropped to her knees and hugged me to her.

“What is it?” I asked.

“She is gone, Mishka,” my mother sobbed. “Your babushka is gone.”

I did not understand why my mother cried so. Sometimes, Babushka Ina took the train to The City to visit her cousin. Once, I had even ridden the train with her.

“She has gone to The City,” I assured my mother. I patted her cheek.

“No, Mishka,” my mother said. “Your babushka has gone to heaven.”

After Babushka Ina went to heaven, my mother began to forget.

She forgot to wash the dishes. She forgot what day to stand in line for macaroni and what day to stand in line for bread.

She cried and cried at night and forgot to take her clothes off to sleep. She forgot to read to me at night. I crawled into bed with her. I could still smell Babushka Ina.

She forgot that Babushka Ina said it was bad luck to cry in your soup, and that vodka and beer were very bad. She sat at the kitchen table and cried and smoked cigarettes and drank.

She never sang again.

My mother forgot to take me to kindergarten, and sometimes she forgot her job at the bakery. Sometimes I went to bed hungry. Sometimes I went to bed alone because she went down to the village at night to meet friends.

I watched her as she sat before the mirror, making herself pretty for a date. Red on her lips, blue above the eyes. “Which ones, little bear?” she asked, holding up one pair of earrings and then another.

She hummed as she pulled on her red coat with the black shiny buttons. She knelt in front of me, hugging me to her. “Be a good boy, Mishka. Lock the door. Don’t unlock it until you know it’s me.”

If I had known he would come, I would never have unlocked the door.

Ever.

His shiny pants and scuffed boots filled the doorway.

My mother pushed me in front of her. “Mishka, say hello.”

“Hello,” I said.

He handed my mother a bundle of flowers, bent down, and pushed his narrow face into mine. “So this is the little man of the house, hey? He’s no bigger than a cockroach.”

His smell made my hand want to pinch my nose.

“Shake hands,” my mother urged, giving me another push. He grabbed my hand and squeezed it, hard.

“Don’t worry, Anya,” he said. “The boy and I will have lots of time to get to know each other.” His smile was big, but did not reach his eyes.

That was how it started.

He took her out. He bought me a radio for company.

“It is a radio,” I said, holding it up for my mother to see. I twisted knobs and held it against my ear. “I can hear the world talking and singing.”

He snorted. “You won’t hear anyone in Russia singing.”

“Why not?” I asked.

“Because, little boy, everyone’s too poor to sing.”

“But we are not poor,” I pointed out.

He threw back his head and laughed. My mother hugged me to her. “No we are not, little bear.”

Soon he forgot to go home. He stayed with cigarettes and bottles of vodka and his scuffed boots next to her bed.

“You’re too big a boy to sleep with your mother,” he said. “Only little babies sleep with their mothers. Are you a baby, Mishka?”

I shook my head. “I am five.”

He tossed my favorite blanket and my fairy tale book onto the bed in the sitting room.

“But my mother needs me with her at night,” I said, twisting the hem of my shirt. My mother would move his boots to the sitting room when she came home from work, and put my blankets back in her room. I knew she would.

When she came home from her job at the bakery, she would bring a day-old loaf of black bread, potatoes and cabbage for soup, and a fresh sticky bun for me.

Instead, she came through the door that night with empty hands and a sad face. “I lost my job,” she said.

“You can’t lose your job,” he said, his black eyes narrow and hard. “How will we eat?”

“Can’t you —”

He cuffed her on the side of the head. I had never seen anyone strike my mother. I waited for her to hit him back. Once, in the village, a bigger boy knocked me down. My mother grabbed the boy and shook him by his collar. The boy’s eyes grew wide with fear and he ran away as fast as he could. Just like he would.

But my mother did not grab him by the collar. She did not shake him until his teeth rattled. She pressed her hand to the side of her face and said, “I’m sorry.”

After that, they sat in the sitting room and drank and smoked and laughed and fought. He did not like me there, sitting on my bed in the corner.

“He’s watching me again, Anya!” he said. “Why is he always watching me?” He stomped across the room and shoved me off my bed. He grabbed my blankets and my book and threw them into the pantry in the kitchen.

“There,” he said, dusting off his hands as if ridding himself of something dirty. “This is where you sleep now.” My mother stood behind him, twisting her hands.

I burrowed into the nest of blankets in the kitchen pantry. My book of fairy tales rested on a dusty shelf with the ghostly circles of the canned vegetables we no longer had. After days and then weeks, the beautiful golden firebird on the cover of the book was smeared with grease; on another shelf lay a pile of scrap paper, and my favorite pencil. When I couldn’t sleep because of cold or anger, I drew pictures. Drawings of firebirds, a terrible witch named Baba Yaga, houses walking on chicken legs, talking dolls, giants, and wolves with wings.

Their voices rose and fell beyond the pantry door.

“Why can’t you see he’d be better off in an orphanage?”

“I can’t send him away!”

“You can’t afford to feed yourself,” his voice said. “Besides, I don’t like him. He’s odd.”

“There’s nothing wrong with him.”

Glass shattered. “It’s him or me, Anya.”

“No! Please don’t ask me …”

Another crash. The sound of shoving, angry feet on the floor.

“You stupid woman!” A slap.

“Don’t!”

A crash. A scream. A thud. A moan.

Quiet.

The cold of the pantry floor pushed its way up through my pile of blankets. I shivered and watched the plume of my breath in the air. I was a dragon. I was a firebird. I was not a man who smelled and shouted and blew cigarette smoke through the two holes in his nose.

I pulled my black radio from beneath the blankets and raised the shiny silver antenna to attention.

“… thousands unemployed, homeless, and starving. Alcoholism ripping the fabric of our great society …”

“But I am not homeless or starving,” I said to the voice in the radio. “I have my mother, my blankets, soup with cabbage.” True, we no longer had bread and sausage with our shchi, our cabbage soup. And it had been weeks since my mother had worked. But she still smiled (although less often now) and called me her little bear.

I turned off my radio. I folded first one blanket and then the other just so. I pulled on the Famous Basketball Player shoes my mother and Babushka Ina gave me last Christmas. My toes pushed against the ends of the shoes. I could no longer wiggle my toes.

I stood in the doorway of the pantry, listened, and sniffed. Was my mother cooking kasha or was she crying? Was he yelling, calling her a stupid, lazy cow, or was he gone? Sometimes after a big fight like last night, he would leave. And for a short time, everything would be as it should: kasha for breakfast, my mother smiling just a little. “Come keep me company in the breadline,” she’d say. Or “Let’s practice your reading,” or “Tell me a story, little bear.”

I heard angry voices shouting from the television. I smelled cigarettes. I peered into the sitting room.

“So,” his voice said. “The little cockroach finally crawls out of his hole.”

He lay sprawled across the couch, his ugly feet bare, a glass resting on his fat belly.

“Where is my mother?” I asked. My eyes darted from the sitting room to the bedroom and back to his face.

He did not take his eyes from the snowy screen of the television. “Gone,” he said. “She is gone.”

My heart thumped and thumped against my chest. “When will she be back?” I whispered.

He turned from the television, and eyed me for a long moment, like a cat eyeing a mouse. “Never,” he said.

I waited and listened and watched for my beautiful mother.

I listened for the click of her heels coming down the hall. I watched for the bright flash of her red coat.

When he left at night, I searched the apartment for clues. If she took this, it meant she would be back in a week. If she took that, it meant she would be back any day.

Everything was where it had always been, except my mother and her red coat. She was gone. Her coat was gone. She must have gone farther to find potatoes and cabbage for the soup. Or she looked for a new place for us to live, far away from him.

Something winked from behind the trash can in the bedroom. I got down on my hands and knees, stretched my fingers around the paper wrappers and past empty bottles on the floor. My fingers curled around something hard and smooth. I opened my hand. A button from her coat. I held the button up to the light, ran my thumb across its black, shiny surface. And next to the button was a smear of red. Not the beautiful red of her coat but a dark, sickly red. I touched it with my finger. It pulsed like a heartbeat. It whispered my name.

“Why are you grubbing around on the floor, cockroach?”

I tore my eyes away from the whispering, pulsing red and looked up at him.

He kicked at me with the toe of his boot.

I held up the button. “It is from her coat, her red coat.”

“Bah,” he said. “So what? Who cares?”

“She loved her coat,” I said, following him into the kitchen. “She loved the buttons. She would not let the coat be without a button,” I pointed out.

He grabbed a hunk of cheese from the refrigerator. He slammed the door shut. My stomach grumbled. My mouth watered. I clutched the button in my hand.

He looked down at me, his mouth full of rotten teeth and cheese. He cocked his head to one side. “Where do you think that mother of yours is?” he asked.

I shook my head.

He smacked his lips and belched. I laughed. My mother never allowed me to belch.

“I think,” he said, “she went to the city.”

I frowned. “Why would she leave without me?”

He unscrewed the top of a bottle. “Who knows why women do what they do. You’re a useless little cockroach and she’s a lazy, stupid cow.”

I drew myself up tall. I squeezed the shiny black button until it bit into my hand. “She is not lazy and stupid! You are!”

My head slammed into the kitchen floor and a million stars filled the sky.

The next morning, he said, “Get your coat and hat. We’re going.”

“Going where?” I asked. “Are you taking me to my mother?” I picked at the dried blood on my ear.

He grunted and flicked his cigarette into the kitchen sink. “We’re going into the city.”

“But my mother —”

He raised his hand. I jumped back, knocking over a chair.

“Enough about your mother,�

� he said. “Just get your coat and let’s go.”

I followed him to the train station, one step, then two steps behind. Women stood in the breadlines, bundled in coats and scarves and shawls.

My eyes searched hungrily for the red coat. She would see me stumbling behind this bad, bad man. She would run to me, sweep me away. I would show her the missing button. She would hug me to her. “My good Mishka. My brave boy.” We would not let him through our door ever again.

A hand grabbed the back of my neck. “Keep up, boy,” he growled.

My legs told me to run, to run as far and fast as I could from him. His hand tightened on the back of my neck. He shoved me through the train station doors.

“You know where my mother is in The City?” I asked.

“Sure, sure,” he said.

A large, bright eye winked at the end of the train track — the eye of a large beast racing, snaking toward us, hissing and screeching. I grabbed his hand.

He slapped me away. “Stop acting like a frightened little girl.”

I almost laughed. It was, after all, just the train.

He yanked me through the train’s doors and onto a hard plastic seat.

Once, I had been on a train with my Babushka Ina. She had held me up on her lap so I could see the lights of our little village tick, tick past.

He lit a cigarette and snapped open the newspaper. I knelt down and watched our village grow smaller and smaller.

Stay

Stay A Dog's Way Home

A Dog's Way Home The Dogs of Winter

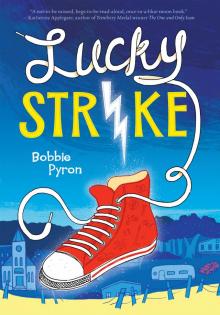

The Dogs of Winter Lucky Strike

Lucky Strike A Pup Called Trouble

A Pup Called Trouble