- Home

- Bobbie Pyron

The Dogs of Winter Page 2

The Dogs of Winter Read online

Page 2

“Wake up.” A hand shook me. “Come on, kid. I don’t have time for this.” He pulled me to my feet and out the door of the train. I followed behind him across the platform, past carts of food — roasted hazelnuts, sausages, whole potatoes wrapped in newspaper — my stomach grumbling, my mouth watering. “Wait!” I called to the back of his tattered coat. But he did not.

Everywhere inside the station were people. They hurried to the trains, they hurried away from the trains. They carried bundles and bags and satchels. They did not look left, they did not look right. They did not look at me as I called again, “Wait!”

Finally, he stopped.

“Is this where my mother is?” I asked.

He laughed.

It was as I had thought. She had moved to The City. She had a good job and a warm place for us to live with lots of food and sweet sticky buns. When we walked up the steps to our fine apartment, she would throw open the door, pull me into her arms.

And she would close the door in his face, for good this time.

He grabbed me by the arm and pulled me up the steps. I stumbled on one stair, then another, scraping my knee. I didn’t care. I would soon be with my mother and all would be as it should be.

We broke into the sunlight, the cold fall air. Snowflakes wheeled overhead, settling on his shoulders and on the toes of his brown boots. He looked up the street one way and down another. “Where the hell is she?” he growled.

I looked up at him and smiled. He had brought me to her. Perhaps he was not such a bad man after all. “Spasibo,” I said. Thank you.

We stood in the falling snow and waited. He smoked a cigarette, then another. I watched for the red coat and rubbed the black button in my pocket over and over with my thumb.

A very dirty boy with no coat or hat or shoes walked over to us. My mother would never let me get so dirty. She would certainly not let me outside without a coat or hat, and especially not without shoes.

The boy tugged on the man’s coat sleeve. He held out a filthy hand. “Please, sir,” he said.

Before I could wonder what the boy wanted from him, the man cuffed the boy on the side of the head. “Beat it, you filthy little beggar. Go bother someone else.”

The dirty boy glared at me, then spat at my Famous Basketball Player shoes.

“Finally.” The man flicked his cigarette to the ground and wrapped his scarf around his neck. He grabbed my arm. “Come on, let’s go.”

I trotted beside him, looking and looking for the red coat. For my mother’s smiling face, her chestnut hair, her outspread arms that would enfold me like angel wings. “Where?” I asked, trotting to keep up. “Where is she?”

“There,” he said.

I stopped dead in my tracks. This woman coming toward us was not my mother. She wore a black coat. A brown scarf covered most of her gray hair. Her arms were folded across her big chest. She did not smile as she looked down at me and said, “So is this the boy?”

I looked from the unsmiling woman to the man. Perhaps she was my mother’s friend. “Are you taking me to my mother?” I asked.

The woman frowned. “I thought you said he has no parents,” she snapped. Her eyes were small and hard like the eyes of the witch, Baba Yaga, in my fairy tale book.

“He’s just a kid,” he said. “He doesn’t know anything.”

The unsmiling woman sighed. “Most of the children in the orphanage don’t know anything either. At least about their parents.”

Orphanage. The word dropped like a cold stone in my stomach. Once on the television news I saw a story about orphanages in The City. None of the children in those places smiled or had mothers. Mostly they cried. They were almost as dirty as that beggar boy, but not quite.

“I cannot go to an orphanage,” I explained to them. “My mother won’t find me there.”

“Your mother isn’t looking for you,” he said.

“She is!” I said.

The woman in the coat that was black, not red, grabbed my shoulder. “Come on, boy. It’s time to go.”

“No!” I jerked away from her hand, a hand more like a claw, a witch’s claw.

I heard my mother’s voice say, Run, Mishka! Run!

I spun away from them, looking and looking for the red coat. I saw green coats and blue coats and gray coats, and many, many black coats.

He grabbed me, twisting my arm. “Come on, you brat.”

And then I saw it: a flash of bright red. I tore away from his grasp, ripping my coat from my body. Run, Mishka! Run!

I did. I ran as fast as I have ever run toward that flash of red as it descended down the steps to the railway station. I dashed this way and that through the train station, looking in the crowds of hurrying people for the red coat. Finally, I saw it, standing in a line like a beacon, waiting to board the train.

Gripping the button in my pocket, I pushed through the sea of brown, black, and gray, desperate to keep sight of my mother. The wave of brown and black and gray swept me onto the train.

I spotted a small figure in a red coat and chestnut hair beneath a blue scarf sitting in the front. I wound through a forest of legs, touched the red sleeve, held out the button, and smiled.

The train lurched. I staggered back against brown and black and gray. “Watch it,” someone said, pushing me upright.

I looked at the face of the woman in the blue scarf. Her hair was black, not chestnut. She did not smile. The coat was not even red.

She was not my mother.

The train lurched. A voice announced, “Leningradsky Station.”

I sat up, rubbed my eyes, and uncurled myself from the train floor. The wave of brown, black, and gray coats spit me out of the train and carried me along the bright corridor. Was it still day or was it night? I had no idea. In the underground world of metro tunnels, it never changed.

I followed the stream of people up the long staircase, through the clicking turnstiles, then up the wide steps to the street.

Cold slapped me in the face. Stars glittered overhead in the night sky. I reached up to pull my hat down over my ears. My hat was not there. My coat was gone too. He had pulled it off as I tried to get away.

I thrust my hands into my pockets and looked for anything familiar. I saw no bakery; I saw no butcher’s shop where my mother bought bones for the soup. I did not see our apartment building squatting at the top of the low hill.

I shivered in the night wind. I trudged back down the steps to the underground, where it was always daytime and not as cold. I spotted a heat vent underneath a long bench. I crawled under the bench and curled up around the warm air. I splayed my fingers across the grate, thought about the red coat that was not the red coat, and finally slept.

Something grabbed my foot and yanked me from my sleep.

“I’ve almost got it!” a voice said.

I scrambled back, pulling my foot away, and banged my head on the bottom of the bench. A dirty, narrow face with beady eyes glared at me.

A giant rat had come to eat my foot! I shrank back in horror and tried to make myself as small as I could.

A grimy hand reached for me. It was not a rat. It was a boy!

Another face appeared next to his. A bruise shadowed a dark eye. Its husky voice said, “Why, it looks like a little bear all curled up in its winter den.” Holding out a hand, it said, “Come here, mishka, little bear.” The voice and the hand belonged to a girl.

I looked from the girl to the rat-faced boy and back. She called me little bear. My mother called me little bear.

“Have you seen my mother?” I asked the girl. “She is looking for me.”

The rat-faced boy laughed. “Yeah, right. All our mothers are looking for us.”

The girl jabbed him in the side with her elbow. “Shut up, Viktor,” she snapped. She peered at me under the bench. “Did you lose your mother on the train?”

I shook my head. “I lost her before,” I said.

The girl nodded. “It’s been a long time since you’ve seen her?”

I blinked back tears. “But she is looking for me,” I said.

The girl held out her hand again. “She won’t find you hiding underneath a bench,” she said. “Come on out, little bear.”

Four children encircled me. I could not tell their ages or their size. Their mothers dressed them in cast-off clothes either many sizes too big or too small. Still, where there were children, there were adults. They would tell me how to find my mother.

“My name is Tanya,” the girl said. She pointed to the rat-faced boy. “That’s Viktor.”

A girl with a baseball cap and a cigarette tucked behind one ear jabbed her thumb at her chest. “I’m Yula and I make more money than anybody else.” She pointed to a dark-skinned boy with dreamy eyes, “Mr. Glue Head there is Pasha.” Viktor snickered.

“My name is Mishka Ivan Andreovich and I am five years old.” I stood as tall as I could in my Famous Basketball Player shoes. “I have to find my mother. We live in the town of Ruza.”

Rat-faced Viktor laughed and waved me away like an annoying fly. “We’ve all lost our mothers, stupid.”

Tanya glared at him. “What do you know? Maybe his mother is looking for him. Ruza is a long way from here. If we bring him to her, she’ll probably give us money.”

“I don’t believe in mothers,” Viktor said. “There is no mother looking for him, and he’s too small to keep.”

I started to ask him how he could not believe in mothers. Everyone has a mother, even mean, dirty children. I started to tell him about the red coat and the black button and how my mother read to me every night from the book of fairy tales, and how everything changed after Babushka Ina went to heaven and my mother began to forget and he came into our house, when a low, lazy voice from the shadows said, “As always, Viktor, your imagination is limited by your pea-sized brain.” The rat-faced boy flushed. His eyes shifted nervously from side to side.

“He is useful to us precisely because he’s small.” The voice stepped from the shadows, cigarette smoke streaming from his nose.

The tribe of children fell silent and stepped back from me. I rubbed the black button in my pocket with my thumb over and over.

He flicked the cigarette to the floor and stepped close. He took me by the shoulders, turning me this way and that. “How old are you?” he barked.

“Five,” I whispered.

He nodded and pinched my arm. “Small for your age. Even better. And those big brown eyes will grab the ladies every time.”

He wore the coat of a policeman. True, it was torn and filthy. It had no buttons. And his pants and shoes did not look like policeman pants and shoes. Still, my mother always told me the militsiya’s job is to help.

“I’m lost,” I said. “And I’m hungry.”

He squinted through the smoke. “So?”

“I need to find my mother. She’s worried about me.”

He spat something dirty onto the ground. “What do I look like, a policeman?”

“Yes, you do. My mother always told me to ask a policeman for help if I got lost. So I am asking you.” I gave him my best smile.

The girl named Yula howled. “Rudy, militsiya!”

The others took up her chant. “Rudy, militsiya! Rudy, militsiya!”

I turned to Tanya. “Please,” I said. “Take me to your home. Your mother will understand.”

She nestled in close to Rudy’s side. He draped one arm across her shoulders. With the other, he swept his arm wide, taking in the soaring arches, the grimy pillars, and the dirty, tattered children. Some followed passengers off the train, begging, while others were asleep on the cold, hard floor, their arms outstretched, palms up, begging even in sleep.

“Do you see any mothers here?” he asked. “Do you?”

I looked from Rudy’s cruel gray eyes, to Tanya. She leaned her head on Rudy’s shoulder, her eyes filled with pity. “We have no mothers, Mish. This is our home.”

“Here’s what we’re going to do,” Tanya said, leading me up the long stairs to the world above the underground. “We’re going to say you’re my little brother. My sick little brother. And we need money to buy you medicine.”

I frowned. “That’s a lie. I’m not your little brother. My mother told me to always tell the truth.”

Tanya sighed. “Haven’t you ever played pretend, Mish?”

I nodded, although I had never played pretend with anyone else.

“So that’s what we’re doing. We’re pretending we’re brother and sister and you’re sick. I bet you’re real good at pretending to be sick.”

I clutched my stomach and moaned.

“Good! Good!” she said, clapping her hands. “Now let’s hear you cough.”

I hacked and spat. “Like that?” I asked.

She hugged me to her. “Just like that,” she said.

“And if I’m really good at pretending, will you help me find my mother?”

She mussed my hair. “Sure, Mishka.”

So there on the streets of The City, on a cold fall day, I performed. I clutched and moaned and coughed and spat. I squeezed tears from my eyes while Tanya grasped at the people, all the people hurrying by. “Please help us,” she’d say, plucking at a coat sleeve, a string bag. “My little brother is sick! We need money for medicine.”

Most dropped coins in her outstretched hand without bothering to stop. Soon the coins clink clinked in her coat pocket.

One man shoved a bill in her hand and said, “Get him a coat, for God’s sake.”

One woman gave us both a yellow balloon with a ribbon on it.

No one asked where our mother was.

By afternoon, I was too hungry to play pretend. “We have plenty of money now to eat whatever we want,” I said.

Tanya jingled the coins in her pocket. “We don’t use money for food, silly,” she said. “We use it to make us happy.”

“Food will make me very happy,” I pointed out.

“We steal food,” she said. “It’s easy enough.”

My mouth dropped open. I stepped back, shaking my head. “I can’t steal. Stealing is wrong.”

“Who says?” Tanya shrugged.

“My mother says.”

Her eyes blazed. She slapped the side of my face. “Wake up, Mish. Do you see your mother here? Do you see my mother here? Or Yula’s mother, or Viktor’s, or Pasha’s?”

I wiped at my wet eyes and shook my head.

Her face softened. She smoothed my hair. “I’m sorry,” she said. “But you need to learn. We make our own rules. And our number one rule is to do whatever we must to take care of ourselves. If that means steal, we steal. If that means lie, we lie. Understand?”

I nodded. I touched the bruise blooming on my cheek.

Tanya peered down at me, hands on her hips like my mother did when she was about to tell me what a troublesome boy I could be. “Okay,” she sighed. “I’ll get you food.”

She scanned the plaza. People filled the benches, tilting their faces up to the fall sun, paper bags at their feet. She pointed at a fat man sitting on the edge of the fountain. “That man will need a lot of food to fill his big, fat belly.”

I nodded. Surely if he knew I was lost and without my mother and very hungry, he would share his lunch with me.

Tanya pinched my shoulder. “Here’s the plan: You pretend you’re playing in the fountain, right? Pretend?”

I nodded.

“Get close to him and splash him good.”

“But,” I said, “that will make him angry and then he won’t share his lunch with us.”

Tanya rolled her eyes. “God, you’re stupid. The whole point is to make him angry! Angry enough to chase you. Then,” she said, grinning, “I’ll steal his lunch.”

I looked at Tanya and at the fat man sitting on the edge of the big fountain. The brown paper bag at his feet bulged like his belly.

The fat man fed us well. My Famous Basketball Player shoes were wet and so were my pants up to my knees. I shivered as I licked the last of

the sausage grease from my fingers. With my belly full, guilt crept into my arms and legs like a spider and gnawed at my heart. I fingered the button in my pocket. My mother would slap me for what I did.

Tanya stood up and stretched. She jingled the coins in her pocket. “Come on,” she said.

I trotted behind Tanya, following her through the streets, still looking for the red coat. Brown coats, gray coats, black coats. Was that a red coat?

I tripped over something and flew through the air. Tanya yanked me up by my arm. “Watch where you’re going,” she said.

I looked back. I’d tripped over a boy lying on the sidewalk. Was he pretending to be sick too? A fly crawled across his face. He was missing his shoes. Someone would stop. Someone would brush the fly away from his face; someone would gather him in their arms. But no one did. They walked past him and around him and even over him as if he were nothing at all. As if he were a ghost.

“Come on,” Tanya said, jerking my arm, hard.

A gust of cold wind blew scraps of newspaper down the sidewalk, and blew the fly off the sleeping boy’s face.

“Do we go to school tomorrow?”

Viktor laughed and passed the bottle to Yula. She tipped the bottle back and took a long drink. Pasha breathed in and out, in and out of a brown paper bag.

Tanya leaned back against Rudy, her face full of dreams. “The city is our school, Mish,” she said. She opened her arms wide. “The whole wide world is our school.”

I puzzled over this. I wanted to go to school. I loved the smell of my classroom at kindergarten: wet wool, warm chocolate drinks, and bread.

“But I want to go to school,” I said. “I am learning to read and write.”

“That’s because you’re stupid,” Viktor said.

Rudy flicked his cigarette at my feet. “The schools don’t want us,” he said.

“But all children must go to school,” I said. “It’s a law.” A train rattled to a stop. People poured out of the doors, going this way and that, looking at watches, at signs, anywhere but at us. But I looked for the red coat. I looked for the train with the letters RUZA on the front.

Stay

Stay A Dog's Way Home

A Dog's Way Home The Dogs of Winter

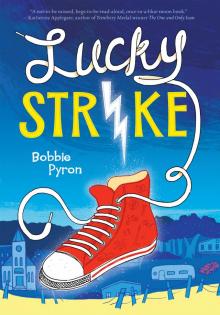

The Dogs of Winter Lucky Strike

Lucky Strike A Pup Called Trouble

A Pup Called Trouble