- Home

- Bobbie Pyron

Stay Page 2

Stay Read online

Page 2

“Remember this, Baby,” Jewel says.

Baby cocks his head to one side and listens.

“There are good folks out there.”

“Some bad folks, but mostly good.”

“Don’t ever forget, Baby. Mostly good.”

Baby licks his white paws

over and over and over

tasting every last crumb.

7

Divided

“What do you mean, I can’t stay with my family?” Daddy asks for maybe the millionth time. His voice is a notch higher than the last time he asked.

Dylan clutches Daddy’s leg. My heart pounds in panic.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Trudeau, but that’s the rule at the emergency shelter,” the woman behind the desk explains. “Women and children stay in this building, and men in the shelter next door. It’s for security reasons.”

I look at Mama. Surely she can fix this. Mama is famous for her negotiation skills. Grandpa Bill used to say Mama could talk the chicken right off the bone.

But Mama’s eyes fill with tears. Her nose is red. She’s clutching and unclutching the handle of the suitcase.

My grandma Bess used to say, the hotter the water, the stronger the tea. Let me tell you, right now the Trudeau family is in a heck of a lot of hot water.

I take a deep breath, stick my chin out, and say real importantly, “Our family has to stay together, ma’am.” I hope she can’t see my knees knocking. I look at her name tag. “Becky,” I add.

Becky’s eyes soften. “I wish you could, truly I do, but those are the rules.”

Becky pushes a form across her desk. “Why don’t you start filling this out,” she says, tapping the paper with her fingernail, “while I get a few things you’ll need.” She smiles and nods. “Then we’ll get you all settled. You’ll feel better after that.”

“Oh,” she says, pulling out another form. “Fill this one out too. It’s for Hope House, a family shelter. We’ll get you on their waiting list right away, so you can all be together.”

Hope House. I like the sound of that.

Daddy bends low over the desk to fill out the forms. I swallow hard and stroke Dylan’s hair. A fluorescent light buzzes overhead. I can smell fried onions and Pine-Sol cleaner. Down a long hallway, a baby cries.

Becky returns with two plastic bags. She hands one to Mama and one to Daddy. “Towels, blankets, toiletries, things to help you settle in,” Becky explains.

Dylan whimpers a tear-laced, watery sniff.

“Oh, I almost forgot.” Becky kneels down in front of Dylan and hands him a paper bag. She smiles. “Some things just for you.”

“Really?” Dylan opens the bag. Inside are coloring books, crayons, puzzle games on sheets of paper, and a paperback book.

“Look!” he says, holding out the bag like it’s trick-or-treat. “Just for me!”

Becky looks right into my eyes. “I’m sure you’re a wonderful big sister and will help him enjoy his treats.”

I nod. “Yes, ma’am.”

“Mr. Trudeau,” Becky says in a gentle but firm voice, “you head on over to the men’s shelter. They’ll get you all settled into a nice room.”

Becky touches Mama’s arm. “Let me show you around.”

Dylan takes my hand. “I’ll share my crayons with you,” he says, smiling up at me.

I straighten the superhero cape on his shoulders. “Thanks,” I say. “I’ll read that book to you, if you want.”

“Yay!” Dylan skips between me and Mama as we walk down a long hallway lined with doors, some open, some closed.

I remember Daddy. He’s standing there looking lost. I raise my free hand and wave.

“We’ll be back, Daddy!” I call.

As we walk down the hall, I try not to look inside the rooms that have open doors. I know it’s rude, but I can’t help it. My curiosity gets the best of me.

Inside one room, a woman sits on her cot writing in a notebook.

Next door, a lady holds a tiny baby close to her chest, rocking it back and forth.

Inside another room, a woman runs a comb through a girl’s long black hair while two little boys play with cars at her feet. The girl looks at me and smiles. I smile back and hurry after Mama.

“You’re lucky,” Becky says as she stops in front of a closed door all the way at the end of the hall. “This room has a nice, big window.” I see in my mind the tall, sun-filled windows in our house back home.

Becky pulls out a ring with about a million keys on it. She slips a key in the lock and pushes open the door.

At first, I don’t see the window. I see two cots piled with blankets and pillows, an old chest of drawers, and a chair. That’s it.

Then I see it: a small window high above our heads.

I hear Becky telling Mama about the bathroom down the hall and what time they lock the shelter doors at night and where the community dining room is.

But I’m looking at the piece of blue outside the window and wondering how this can be the same sky, the same piece of blue, I knew back home.

8

Fancy Dog

Later

in their park

under a sun-dappled sky,

Baby sees a fancy dog,

a live-inside kind of dog.

Baby sees this dog almost every day.

Every day

the fancy dog and her person

come from the exact same direction

at the exact same time,

the dog leading the way, tail up,

tongue out

with anticipation.

They walk the same path through the cottonwood

trees,

circle the duck pond twice,

then stop at the same bench where they always stop

and sit.

Baby remembers how it was to live in the same place,

take the same walk, see the same things

every day.

“Our home is everywhere!” Baby yips with happiness.

Parks. Streets.

Inside tumbledown buildings.

And now in this park, full of delicious smells

and friends:

Ree and Ajax

Linda and Duke

Jerry and Lucky.

“We are always together now, always

me and my Jewel.”

The fancy dog’s person unclips the leash from the

dog’s collar.

The collar sparkles like dew on grass.

The dog cocks her head,

considers the delights held

in a mud puddle.

Baby runs through the puddle, splashing mud

on the fancy dog’s perfect white coat.

The not-as-fancy-now dog’s person frowns.

She clips the leash on the sparkly collar.

Baby does not understand leashes.

Jewel walks, Baby walks beside her.

Jewel tells Baby to stay, he stays.

Why would he do anything else?

Baby hears the fancy dog sigh.

He watches as the dog and her person

walk the same path

through the cottonwood trees,

past the swings

back the way they always go.

But now,

the fancy dog walks behind,

feet dragging,

tail down.

Baby feels sad for the fancy dog until

he hears Jewel call, “Let’s go, Baby.”

Baby’s heart leaps. His two favorite words!

New places, new people,

one lucky dog.

9

We All Look Up

Let me tell you, living in a shelter means you spend a lot of time standing in line and waiting. First, we stand in line and wait to take showers, then we wait to wash and dry our clothes. Mama says it’s a good way to meet people, though. Back home, when we’d go to the Piggly Wiggly to do our grocery shopping, by the time we got to the checkout lady, Ma

ma was best friends with everybody in line. And she loved going to the Just Like Home Laundromat to catch up on all the town gossip.

Here, though, people don’t seem so friendly or talkative.

By the time we get ourselves and our clothes clean, there’s a new lady at the front desk. Her name is Jean. She smiles a lot. She gives us meal tickets for the Sixth Street Community Kitchen. “It’s nothing fancy, but it’ll fill you up,” she says with a laugh. She also gives us directions to the Christian Center, where we can get winter coats, gloves, and hats. “Just show them this,” she says, handing Mama a slip of paper with a bright-green stamp on it, “and they’ll let you pick out a few things for free. Can’t beat that!” Jean has a lot of enthusiasm for her job.

We meet Daddy out front. Dylan wraps his arms around Daddy’s legs like he’s never going to let go. Daddy looks so tired. My heart hurts. I go stand next to him, touch the sleeve of his jacket. “Hey, Daddy,” I say.

Daddy gives me a quick, sideways hug. “Hey, peanut,” he says. “Take your little brother’s hand.” Gently, he peels Dylan’s arms from his legs.

We wait in line for the right bus to take to the Christian Center. I don’t mind the waiting in this line so much. I love looking at those high, faraway mountains.

When we finally get to the Christian Center, we wait, again, while the guy working there unlocks the back room. Mama hands him the piece of paper with the bright-green stamp while Daddy tries to keep Dylan from running in and out of the clothes racks.

The man pushes open the door. “Here you go,” he says.

Mama’s face falls just the tiniest bit. No nice, neat clothes racks in here. Instead, clothes piled up in boxes without rhyme or reason. The room smells like mothballs and bleach.

Mama pulls a smile out of her pocket anyway. “Thank you,” she says.

I’ve never had a real winter coat, and only hats and gloves for fun. We never needed much more than a heavy sweater in Louisiana. After digging through two tall boxes, I find a red wool coat with a hood and pockets. “It’s perfect,” Mama says. “The red shows off your pretty blond hair and green eyes.” Describing my hair as blond is a bit of a stretch—it’s more light brown—but that’s okay. My eyes are, for a fact, green.

After we’ve gotten our coats, hats, and gloves, Daddy says we should walk around and “get the lay of the land.” He said this same thing in Tallahassee, where his buddy Jim had promised him a job; in Baton Rouge, when we stayed with Mama’s cousin; and in Abilene, Texas, where our car broke down. For good. And where Dylan landed in the emergency room with bad asthma, which used up almost all our money.

The wind blows hard and cold. I pull my hood up and take the gloves out of my coat pocket. A little slip of paper flutters to the sidewalk. I pick it up. It’s from a fortune cookie. It says “The stranger you will meet will become your friend.” I snort. I show it to Mama. “Everybody here is a stranger,” I say. Back home, between school and my Firefly Girls troop, I had lots of friends. And the town was so small, there were hardly any strangers.

“Yes, but every stranger you meet is a friend in disguise,” she says, looping her arm through mine and bumping me with her hip.

We stand in line again, waiting, for the Sixth Street Community Kitchen to open. At least Daddy gets to go inside and eat with us. Mama’s talking with a woman behind us who has a little baby with a runny nose. Daddy’s frowning at the Help Wanted ads in the newspaper. Dylan is just about worn completely out, so I keep him close to me and pull his new hat down over his ears.

There are lots of people in this line waiting to eat. Some have big packs on their backs, some push shopping carts loaded with all kinds of stuff. There are old people who don’t talk much (unlike the old people back home), and women telling their kids to behave. People talking, some laughing, bare hands rubbing together to keep warm. The wind carries the smell of buttered bread and unwashed clothes.

Other people—people looking like they have somewhere important to go—don’t look at us. They don’t want to get too close, like our situation—standing in a line to eat—might be catching. I shrink inside my coat. I’m glad everybody here is a stranger.

I see the girl with the long black hair from the shelter ahead of us. She smiles and waves.

I’m just about to wave back when the woman in front of us turns around.

Her silver hair blows in the wind. Where have I seen her?

“Have you seen Sis?” she asks. Her blue eyes dart with worry. Her eyes, the color anyway, remind me of Grandma Bess.

“Um, I’m not sure who Sis is, ma’am,” I answer.

The old woman looks up at the sky. “The Angels are coming in their chariots of wind and ice,” she says.

Okay, that’s kind of weird. Before I can answer, I see something wiggle under the woman’s coat. A little brown, fuzzy head pops out under the woman’s chin. The dog looks right at me and, I can tell by the way his eyes smile, he’s wagging his tail.

“Oh my gosh, he’s so cute!” I say.

The worry leaves the woman’s eyes. She smiles. “This is my Baby,” she says.

The little dog tips his head up and licks her chin.

“Can I pet him?” I whisper.

The woman nods. “Dogs are the best medicine,” she says.

I reach out and stroke the top of his head. It’s warm beneath my hand. He closes his eyes and makes an almost-purring sound of contentment.

I know exactly how he feels. Just for that moment, everything feels normal, even good. My heart is light.

A voice behind us breaks the spell. “Line’s moving.”

I blink. I’m standing in the cold, waiting to eat.

I put my hand in my pocket to hold on to that good feeling of the little dog’s head.

“Thank you, ma’am,” I say. “I do feel better.”

She turns back around. In my mind, I’m already planning on sharing my food—whatever it is—with that dog.

Then I hear a voice at the front of the line say, “Come on, Jewel, you know the rules. You can’t come in with your dog.”

“Please, Rick,” she pleads with the man at the door, “just this one time. He won’t hurt anybody. Why,” she says all in a rush, “you won’t even know he’s there.”

The man named Rick shakes his head. “I’m sorry, Jewel.” He motions for the next person in line to come through the door.

“It’s not fair,” I mutter.

“It’s mean,” Dylan says, rubbing his eyes.

The old woman walks toward us. Her eyes are fixed on the sidewalk. She’s saying something over and over that I can’t hear. But oh! That little dog, Baby, looks directly into my eyes. Like he has all the hope in the world. And for just a minute, for the first time in a long time, I feel a little flicker of hope too.

Miss Jean was right: the food was not very good—canned corn, canned green beans, soupy potatoes, some kind of meat, sliced white bread—but it did fill us up.

As we walk back to the shelter, even though it’s colder than ever and the wind pushes us along the sidewalk, we’re all dragging our feet. We know we have to get back by eight or we’ll be locked out, but getting back also means Daddy goes one way and we go the other.

Then, all of a sudden, Dylan stops dead in his tracks. He looks up into the streetlight. “Look!” he cries.

I can’t make sense of what I’m seeing. White, white feathery things swirling, cartwheeling down from the black night sky. At first there’s just a few, and I wonder if I imagined it. Then there’s more and more, like swarms of white butterflies.

Something wet and cold lands on my cheek. I gasp. “Snow!”

Dylan laughs. He runs this way and that, trying to catch the snowflakes in his hand just like he used to chase fireflies at home.

Mama turns her face to the sky, closes her eyes, and smiles a beautiful smile. “Snow.” She sighs with happiness.

Daddy puts his arm around her and, for the first time in forever, he smiles too.

&n

bsp; We all look up at the wonder of it in the circle of light. Snowflakes swirling, landing, touching cheeks, noses, eyelashes like little kisses from heaven.

10

Listen, Baby Says

The smell of sadness surrounds Baby

inside the warmth of Jewel’s coat.

His heart beats in time

with her footsteps

as they walk up one street and down another.

Past the place where people sleep inside

not outside

like Baby and Jewel.

He can smell the longing in her heart.

“Listen,” Baby says, nudging her with his head,

“listen to the wind in the trees,

the song. We have that.”

Across the street, Baby smells the tumbledown

building

where they slept

when they first came to this city.

That memory leads Baby back to the feel of the

rocking bus

and the hum of the wheels against the road

as he lay curled

hidden

in the bottom of Jewel’s bag.

Curled up in sweaters, socks, a coat,

a little brown bunny missing one eye,

his favorite toy.

The old leather book that holds the smell of Jewel’s

hands,

the book she reads over and over and over

when she’s sad or afraid or

jubilant.

The smaller book she never opens anymore.

The light changes.

The cars stop.

A cold wind blows.

Baby feels Jewel’s heart shudder.

“Listen,” Baby says as he licks the wet, salty tears

from the deep furrows on his Jewel’s face.

“There is nothing between the world

and us.”

Baby feels Jewel’s heart lift.

She looks up into the street light.

She laughs,

closes her eyes

and spins in slow circles

as snowflakes wheel down and around them.

“Oh Baby, my Baby,” she sings over and over

into his waiting ear.

“What a wonderful world.”

The light changes again.

The cars creep forward,

Stay

Stay A Dog's Way Home

A Dog's Way Home The Dogs of Winter

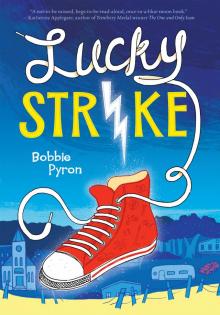

The Dogs of Winter Lucky Strike

Lucky Strike A Pup Called Trouble

A Pup Called Trouble