- Home

- Bobbie Pyron

The Dogs of Winter Page 4

The Dogs of Winter Read online

Page 4

I stood at the top of the low hill. One raindrop, then many, pelted my face. I slid my book under my sweater. I pointed the toes of my Famous Basketball Player shoes down the hill and followed them back to the train station and The City and Leningradsky Station.

It rained for days. Some days the rain was cold and thin; other days it drowned out the sounds from the street above the train station. The rain kept us below ground, away from begging and stealing and food and drink.

The first day, we slept on our beds of newspaper and cardboard. Even Rudy slept when he was not playing some trick on Yula or Viktor. I watched for red coats, chestnut hair, and dogs.

The second day, Tanya refused to steal a woman’s purse and Rudy beat her. Yula left with a man in a gray suit. When she returned later, she had clean hair, a bag of food and beer, and bruises on her neck.

On the third night, I read to everyone from my book of fairy tales. True, I could not read all of the words, but I heard my mother’s voice reading the stories to me well enough. The only sound as I read the story of the Little Match Girl was the clack of the trains and the scrape of Pasha’s cough. Rudy cleaned his fingernails with the tip of a switchblade.

“She was just like us.” Tanya sighed, wiping away a tear when I closed the book. “No one cared, even then.”

“Someone did, though,” said Pasha. “There was that light that lifted her up and took her away.”

“It was God,” Yula said. “It was God who took her away.”

“Or angels,” said Tanya. “It could have been one of God’s angels come to take her away.”

Viktor snorted. “Where were the angels, where was God when she was starving and freezing? Where were they when she was turned out on the street?”

Everyone looked at the floor.

“I’ll tell you where the angels are,” he said, snatching my book from my hands. “They’re in here with all the other fairy tales. That’s all they are: fairy tales!”

I jumped at his outstretched arm. “Give me back my book,” I cried.

He held the book higher. “Jump, little mouse,” he sneered.

I jumped and I jumped as high as my Famous Basketball Player shoes would take me.

“Look, he’s a circus mouse,” Viktor said. “A stupid, little circus mouse!”

Tanya leapt to her feet. “Give Mishka back his book, Viktor, or I swear to God —”

“Swear to God all you want, Tanya,” Viktor said. His face was twisted in a way I had never seen. “It won’t make any difference.” His face glistened in the light of an oncoming train.

“God’s not here,” he went on. “God is just a stupid, stupid fairy tale.” And with that, he flung the book high. It soared above our heads and our outstretched hands. It flew through the air, the pages lifting like lovely white wings. The book was an angel, a firebird. It hung for an instant in the shining white light of the train and then fell beneath its wheels.

Tanya punched and kicked Viktor. “See what you’ve done!” And because Yula does what Tanya does, she took off her shoe and smacked Viktor in the face. Pasha retreated to his bag of glue.

After the train pulled away, I crawled over to the edge of the platform. There, in a heap, lay the remains of my book.

I started to scramble down to the dirt when a hand grabbed the collar of my sweater and pulled me back.

“No,” Rudy said. “Are you too stupid to see? A train’s coming.” And indeed there was.

Rudy leapt down to the dirt. His boots sent up little puffs of dust. The eye of the train grew larger and larger.

As if he had all the time in the world, Rudy picked through the remains of the book. He examined pages as if he were shopping for vegetables on a summer afternoon. He squinted at the pages through the smoke of his cigarette.

The light of the train grew brighter and brighter. The whistle screamed.

“Rudy! Get out of there!” Tanya cried. Viktor’s eyes were as big as the train’s headlight. My heart thundered down the tracks with it.

Rudy stuffed a handful of pages in his coat pocket. The train was now in the station entrance. The whistle shrieked again. The brakes screamed.

Rudy flicked his cigarette at the rushing light. And with all the grace and disdain of a put-upon cat, he leapt to the platform. He dusted off the knees of his black pants. Without a word, he pulled out the pages from my book of magnificent tales and handed them to me.

“Screw the rain,” he said. He took Tanya’s hand and they disappeared into the crowd.

The rain stopped. The days grew cold. I shivered in my sweater and hatless head and mittenless hands. The people in the streets rushed from one place to another to escape the cold. They did not want to stop long enough to reach in their pockets.

The cold and our empty pockets infuriated Rudy. “Why do I waste my time with you worthless pack of dolts,” he said. “You’re useless. Useless!”

He spat at my feet. “You particularly. You think just because you’re little and you’re younger than the rest, you don’t have to pull your share? You think you’re too good to steal.”

“Come on, Rudy,” Tanya said, touching his shoulder. “Mish doesn’t eat much.”

Rudy slapped her hand away. “And you,” he roared. “You think you’re too good to go with men, do you?” He shook Tanya until her teeth rattled. “It’s time, Tanya. Just you wait and see.”

Pasha coughed and coughed. Rudy whirled on him. “Stop it! Stop coughing!”

Pasha wiped his nose with the back of his hand. His hand came away streaked with red.

On warm days, Pasha and I begged in the parks and squares in hopes that the sun would bring the lunch eaters outside. But not so many came out anymore, and if they did, they were reluctant to part with their money.

“Soon we will leave the train station,” Pasha said.

I watched a brown and black dog approach a woman and her small child sitting on a bench.

“Why would we leave?” I asked.

“When winter comes, the police make us leave the station.”

The dog wagged his tail and grinned up at the woman and child.

“They say too many bomzhi and vagrants stay in the train stations in the winter to keep warm.”

The child laughed and clapped her hands. The mother ignored the dog.

“But we aren’t bums,” I said. “We are children.”

“Bomzhi, vagrants, street children — it’s all the same to the militsiya. We’re cockroaches, all of us. We have to be driven out.”

The dog laid his head in the mother’s lap and gazed up at her, his whole body wagging back and forth. I held my breath.

“We have places we go in the winter to keep warm,” Pasha said.

The woman smiled and petted the dog’s head. I laughed and clapped my hands.

“What kind of places?” I imagined the police taking us to places with blankets and hot soup and coats.

“Underground,” he said. “Next to the steam pipes, where it’s warm as toast.”

The woman broke off part of a sandwich. She handed it to the child, who fed it to the dog.

The dog took the chunk of bread and meat gently from the child’s small hands, and then licked the child’s fingers clean.

I rubbed my finger over and over the black button in my pocket.

Pasha punched me in the arm in a not-mean way. “It’s not so bad, Mish. It’s warm and mostly dry. People feel sorrier for us and give us food. Sometimes the church people come to the plaza and feed us soup and bread. Sometimes they even bring cast-off clothes and shoes.”

“Is it dark down there?”

Pasha shrugged. “Sure, but we have plenty of candles and stuff. It’s fun! A lot more fun than my old home in the countryside. All we had to eat was the stuff we fed the cows and the goats. Here it is much better.”

“What about your mother?” I asked. “She must be looking for you.”

Pasha flicked the side of his neck with his finger. “She was a drunk. So was my father. As long

as they had vodka and each other to yell at, they didn’t care about me or my brothers and sisters. The last time my father beat me, I stuck him in the belly with a knife and left.”

I sucked in my breath. “You stabbed him?”

Pasha nodded.

As much as I hated him, I could not imagine sticking the bad man in the stomach with a knife.

A man with brown boots and shiny buckles dropped a coin at each of our feet. “Thank you, sir,” I called to the legs and boots walking away.

Pasha flipped his coin in the air and caught it in his teeth. I laughed and clapped. “Do it again,” I demanded. And he did.

The brown and black dog rose from the feet of the little girl. He shook himself and then trotted across the park as if he had an important appointment to keep.

The days grew colder and there were more coats to watch. But I did not watch the coats so much anymore. I watched the dogs. They were everywhere — curled up in doorways, sleeping on heat grates, riding the trains, crossing the streets one way and then the other. They begged, they stole. Sometimes they found a kind person and sometimes they were cursed and spat upon. They were just like us, only they were not like us at all. I watched the dogs steal from the sausage cart or from the lunch bags left on the ground. I watched them beg from women and children and old men. I watched them tip over garbage bins behind butcher shops and grocery shops. And always, always, they shared. The small ones ate, the sick ones ate, the old ones ate. That is how it was with the dogs.

On a hard day, a bitter cold day, I sat huddled next to a steam grate in the sidewalk. The cold made my eyes stream tears. I told myself they were not tears for my mother. They were not tears for the weeks it had been since I had slept in a bed and taken a bath. Perhaps it had been months or only days. I didn’t know or care anymore. The tears were only for the cold. I bowed my head and rested it on my knees.

Something warm pressed against me. Warm breath stroked my cheek. I lifted my head. There beside me stood a large brown and black dog.

The dog sniffed my hair and ran his warm, wet nose across my cheek and ear. I held my breath. Did the dog think I was something to eat?

Satisfied, the dog curled up at my feet next to the steam vent with a sigh and closed his eyes.

We sat like that together, the dog and I. People rushed past us and around us and stepped over us. A woman in a blue coat stopped and handed me two coins. A man in a black coat and white collar gave me his sausage sandwich and hurried away. The dog wagged his tail hopefully. I broke the sandwich in half and shared.

Coins dropped at my feet and in my hand. One coin, two coins. The dog and I trotted across the street to the potato man’s cart. The coins jingled in my pocket.

“Please, could I have two potatoes?” I said, holding out coins. The potato man fished two plump, hot potatoes from the metal pan. He handed them to me in a piece of newspaper. I handed him the coins. He studied me for a minute. One eye looked me up and down while the other eye wandered off to a more interesting scene far to the side.

He grunted and fished out another potato. “For your dog,” he said.

I laughed. I could not believe my good luck! Three potatoes! I heard my mother say, Remember your manners, Mishka.

“Spasibo, sir,” I said. “Thank you very much.”

Two hot potatoes to warm my hands and another in my pocket. Two hot potatoes to fill my belly.

The dog and I trotted back to the steam grate. I took the potatoes from my pockets and started to stuff one in my mouth. The dog let out a low woof. He wagged his tail.

“Please forgive me,” I said. I broke the potato in half. He took it gently from my fingers and swallowed it in one gulp.

And still, I had two warm potatoes. I smiled at the dog. I reached out and touched his shoulder. “You’ve brought me luck today,” I said. He licked my fingers. I laughed. “I’m going to call you Lucky.”

Lucky stretched and sniffed the air. He looked at me and then trotted off.

“Wait!” I cried. I dashed off after him, the potatoes bouncing in my sweater pockets.

He looked over his shoulder and slowed to a walk. I ran up beside him. My breath came in frosty puffs. I had not run in a long time. We children mostly sat and lay with our hands outstretched.

“Where are we going, Lucky?” I rested my hand on his shoulder.

I followed him to the corner of two busy streets. Lucky sat down and looked up and down the street. A child on the other side of the street dressed in rags and too-big shoes darted in and out of traffic. Tires screeched and horns blared. I had seen Pasha and Yula play this game of chicken before with the cars.

“That girl is stupid,” I said to Lucky. “My mother said to always wait for the light to turn green.” Lucky looked up at me and wagged his tail in agreement.

We crossed the street when the light turned green. We trotted past empty buildings with their windows either broken out or boarded up. We trotted past big, shiny buildings with fake women in the windows wrapped in warm fur coats.

We trotted past other dogs sleeping in patches of warm sunlight. Sometimes they opened their eyes and barked a greeting. Sometimes they slept on.

We passed other children begging and sleeping on newspapers or sitting in doorways drinking from bottles. Lucky swerved around two older boys fighting on the sidewalk. One tried to grab my arm. “Hey, you,” he snarled.

Lucky whirled and growled, showing the boy long white teeth. The boy backed away.

Finally, we stopped outside a tumbledown shop at the end of a long alley. It may have once been a bakery, or a barbershop, or a grocery store. Now, it was nothing but bricks and weeds.

Except, it was where Lucky was going.

He looked at me. Then he went around to the side of the building. He let out a low bark. And then he disappeared through the weeds and through bricks.

I gasped. How could that be? Was he a ghost?

Then I heard one bark, then another bark. I walked closer to where Lucky had disappeared. I heard a high whimper and a soft mewling.

I pushed aside the weeds and laughed.

Lucky was not a ghost dog. He had not walked through the brick wall. There, covered up by the weeds and rubble, was a small opening in the wall. An opening just big enough for a dog or a boy to squeeze through.

“Lucky,” I called into the dark opening. He answered with a bark.

Two shining brown eyes and a black nose appeared in the opening.

Woof, Lucky said, and then wheeled away into the dark.

I looked up the alleyway. The two fighting boys walked past, still arguing. Fat, white snowflakes drifted lazily down onto my head. I peered into the dark place where Lucky had gone.

I could walk back up the alley and across the street and past the other dirty, sleeping, fighting, begging children and back down to the train station where Pasha would be in his own dream place with a brown paper bag on his lap and Viktor with his rat face and Tanya with her sad eyes and Yula with her cigarettes and men in dark suits.

I dropped to my knees, wriggled through the opening that was just big enough for a dog or a small boy, and slipped into the pocket of darkness and onto the dirt floor.

Slowly, slowly my eyes adjusted to the dark. The weeds outside the building let tiny bits of light in through the small opening.

The light caught an ear here, a pair of eyes there, and there. And over there.

I froze.

Lucky nudged my hand with his wet nose. Woof!

I heard small yips and whimpering from one corner. Lucky tugged on my sleeve.

I followed him through the dark over to the corner. And in that corner, resting on top of a pile of rags and newspapers and dirty blankets, lay a mother dog with her puppies.

“Oh!” I cried. “Look at the puppies!” I reached out a hand to touch them. The mother dog growled. Lucky licked the side of her face and nuzzled the puppies with his nose.

“Is that why you brought me here?” I asked him. “To see th

e puppies?”

Lucky pawed at my pocket — the pocket that still held two potatoes.

I took one potato from my pocket and broke off a piece. I handed it to Lucky. The mother dog whimpered. Lucky dropped the potato chunk in front of her. She snapped it up in one breath. Lucky looked at me as if to say, Go on, then, give her some more.

I broke off another chunk of potato and stretched my hand out to her. I broke off another piece and another. She licked the last of the potato from my fingers. Then she settled her puppies against her belly and let them eat.

I sat back on my heels and smiled. “You’re a good little mother,” I said. “And you, Lucky, are a good father.”

I turned to look for Lucky, to tell him what a good father he was to provide for his family.

I froze.

Dogs surrounded me. Brown dogs, black and white dogs, a small scruffy dog with a badly torn ear. A brown dog with a silver face and soft eyes limped from the corner. Lucky pressed close to me and wagged his tail.

“Hello,” I said to the dogs. “Are you hungry too?”

The dog with the torn ear yipped and did a little dance.

I laughed. I broke off a piece of potato and tossed it to him. And then I fed the others. After all the potato was gone, the dogs pressed close, sniffing my clothes, my ears, my hair. The mother dog rose from her sleeping puppies and washed my face with her tongue. I rolled in the dirt, laughing. “No, stop! That tickles! That’s slobbery!” She licked me all the more. A black dog with patches of white on his legs and back lowered his chest, his hind end stuck in the air. He cocked his head to one side and wagged his tail.

I rolled to my hands and knees, dropped my chest and stuck my bum up in the air. “Woof!” I said. I wagged my bum from side to side. The black dog with the patches slapped one paw on the ground. I slapped my hand and laughed. The old dog watched us with the pleasure of a grandmother.

The weeds rustled at the hole in the wall. In the weak light, I could see something pushing its way through the opening in the bricks. All the dogs stood at attention. I stood too and moved closer to Lucky.

Stay

Stay A Dog's Way Home

A Dog's Way Home The Dogs of Winter

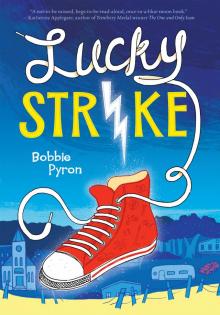

The Dogs of Winter Lucky Strike

Lucky Strike A Pup Called Trouble

A Pup Called Trouble