- Home

- Bobbie Pyron

The Dogs of Winter Page 5

The Dogs of Winter Read online

Page 5

Something dropped lightly to the dirt floor. I squinted into the weak light. That something was a dog.

The dogs pinned their ears back and whimpered their greetings. The little mother dog and the dog with the ripped ear crouched before this dog and licked his chin and the side of his face. That was when I noticed the dog had something in his mouth: a long, thick sausage.

The dog dropped the sausage in the dirt. He seemed to barely notice as the dogs tore pieces of the meat. His eyes were fixed on me.

I pressed closer to Lucky. All of a sudden, I felt like a little mouse in the wolf’s den.

The dog stalked over to me. Lucky stepped back.

“No!” I whispered. But before I could hide behind Lucky, the new dog, the leader dog, circled my legs. He sniffed the backs of my legs and my filthy pants and my sweater pockets that once held two warm potatoes. He pushed his nose into the palm of my hand and read it like a gypsy. He sat in front of me and studied my face.

“I’m Mishka Ivan Andreovich,” I whispered. “I am five years old and I won’t hurt you.”

The dog trotted over to the pile of puppies. He sniffed each one from the tips of their little noses to the ends of their tails. When he was satisfied I had not harmed them, he trotted back over to the opening. Without a backward glance, he leapt through and slipped out like smoke.

The one I now called Patches jumped up and out. The little mouse-colored dog with the ripped ear followed as best as his short legs would manage.

Lucky dropped a last chunk of sausage at the paws of Little Mother. Then he too scrabbled through the opening.

“Hey!” I called. “Don’t leave me!”

Lucky stuck his head into the cellar. Woof!

I knelt and touched each of the three puppies gently. “Good-bye, Little Mother,” I said. “I’ll bring more food for you tomorrow. I promise.”

I wriggled through the opening. It was almost dark. Snow blanketed the alley. And at the end of that alley stood the pack, waiting for me.

I ran with the dogs across the streets, past the gangs of older kids drinking, laughing, fighting, and not scaring me one bit. I was with the pack and we ran together.

Finally, we reached the heat vent where I had met Lucky earlier that day. The dogs stood around me panting and grinning.

I touched the top of each of their heads. “Thank you for bringing me home safe,” I said. “We’ll get more food tomorrow, just wait and see.”

I skipped down the subway steps. Wait until I told Pasha and Tanya about the dogs and the puppies! Maybe if they were nice, I’d take them to meet them. Maybe we could all live together in the cellar and not have to go live in the dark with the hot water pipes. We could feed the puppies until they grew fat and strong. We would be a family with the dogs.

I skidded to a stop in front of the big statue of a man riding a horse. I leapt up and touched the horse’s nose. I bowed before the man. “Evening, sir.”

“Well, well, well,” a voice said. I gasped. Did the bronze man speak?

Rudy stepped out from behind the statue. He held a bottle in one hand and the other one stretched out. “The little mouse returns.”

I smiled up at Rudy. “I had the best day,” I said. “I met this dog and —”

Rudy snapped his fingers. “Turn over the money.”

My stomach dropped. Money.

I dug into my pants pockets. I felt two round, smooth things. I dropped the coins in Rudy’s hand.

“That’s all?” he said.

I nodded.

“You were gone all day and half the night, and this is all you have to show for it?”

My heart hammered in my chest. I nodded again. “Yes, Rudy. I used the other money to buy food.”

Rudy cuffed me on the side of my head. “How many times have I told you! You don’t use money to buy food. You steal food!”

“But my mother said —”

Rudy hit me again, this time knocking me to the floor. “I don’t give a damn what your mother said.” He jerked me up off the floor and shook and shook me. “Your mother isn’t here, Mishka. You listen to me, now. You do what I say. Do you understand?”

Rudy shook me so hard, I thought my teeth would fly out onto the floor. “Because if you don’t start listening to me —”

A large woman in a big coat and brown head scarf rushed over to us. She swung her purse at Rudy. “Leave that little boy alone!” she commanded.

She beat Rudy all about the shoulders and head with her purse. “You’re nothing but a bully,” she scolded.

Rudy threw his arms and hands over his head. “Ow!” he cried. “Leave me alone, you crazy old woman!”

I ran as fast as fast could be through the sea of legs and arms and coats to my place under the long bench over the heat vent.

I got up earlier than the rest in the mornings now. I’d slip from beneath my bench just as the first train arrived. The rest slept huddled together for warmth, newspapers for blankets, cardboard for mattresses, and hips and bellies and legs for pillows.

And every morning, Lucky waited for me at the same spot we had met that first day. Some days he was by himself and other days Patches or Rip, the dog with the torn ear, waited with him. But never Little Mother and never the smoke-colored dog, although I did see him watching us. He watched as we warmed ourselves on the grates and in patches of sunlight. He watched as I asked the people hurrying from the cold to the tall glass buildings, “Please, can you spare a coin so we can eat?”

He watched, his coat black and silver as smoke, as I bought sausages and bread and bones from the butcher shop. I was careful to save coins for Rudy. Then we raced to the alleyway and through the opening in the wall and into the dark warm of the cellar and ate like kings and queens. We’d wrestle there on the dirt floor and play tag in the small confines of the cellar. And then we curled up together and slept.

Sometimes when I woke, the smoke-colored dog was there, watching. I would say good-bye to Little Mother and the puppies and to Grandmother, the old dog who watched over the puppies. “More food tomorrow,” I promised.

And every day, Lucky and the others would race with me through the streets and across the plaza to the heat grate across from Leningradsky Station. Just at the edge of the streetlight shadows watched the smoke-colored dog.

And every night, I gave Rudy the coins I had and he said it was not enough. No matter how much I gave him, it was not enough.

“Kopeks!” he spat. “All you bring me are stupid kopeks?” and he’d toss them to the floor.

“Whatever I give the dogs, it is always enough,” I complained to Pasha one night as the trains galloped by. “They never yell at me or hit me or tell me I’m stupid.” I rubbed my ear, sore from another Rudy beating.

Pasha shrugged. “This is the way it is, Mish. It is the life we have.”

And that was true, until the sweep.

Tweeeet! Tweeeeet!

I jerked my head up from my sleeping place, banging my head on the bottom of the bench.

Whistles, voices, legs running this way and that. My heart sank. I must have slept past the first train.

I started to scuttle out from under my bench when I heard a scream. And then a voice. “Okay, all you bomzhi, you sewer rats. Get up!”

More screams and thumps. Tanya’s voice crying, “Rudy! Rudy!” I squirmed back under the bench and made myself as small as possible.

Tall black boots so shiny I could see my face in them marched past my bench. The heels rang out like gunshots on the marble floors. “Grab that kid,” a voice called above me. I squeezed my eyes shut and rubbed the black button over and over.

Tweeeet! Tweeeeet! “Clean the garbage out,” commanded the voice attached to the tall black boots standing just inches away. Someone — perhaps Viktor, perhaps Pasha — cried, “Leave us alone! We’re not hurting anybody!”

Smack! A head hit the ground. I saw Viktor’s hat fly across the dirty floor and off the platform.

I rubbed the butto

n hard. It jumped from my fingers and clattered through the heat vents.

“No!” I cried. I jammed my fingers into the vents.

“What’s that under there?”

A hand grabbed my foot and pulled. “No!” I screamed, jamming my fingers farther into the vents and kicking as hard as I could.

A grunt. A curse. The hand pulled hard. Off came one Famous Basketball Player shoe.

The hand grabbed my leg and yanked. I screamed in pain as the heat vent cut into my fingers. “Mother! Mother!” I cried.

A cruel laugh. A laugh that sounded like him when he told me I was no bigger than a cockroach. “I’ve got a live one under here.”

The tall black boots and big hands were attached to a man in a policeman’s uniform. But this could not be a policeman. My mother had always said policemen helped you when you were lost. And hadn’t I been lost for such a long time?

I opened my mouth to tell the policeman this when he spat in my face. “What a filthy little beggar.” He threw me over his shoulder like a sack of potatoes. “It’s to the orphanage for you.”

“No!” I screamed. “Put me down! Put me down!” I pounded on his back with my fists, which only made him laugh. On the floor I saw Viktor holding his bloody head and Yula kicking a policeman. His baton cracked against her shoulder.

The policeman carrying me turned and my world spun. He started up the stairs.

And then something slammed into him. A whirling, kicking, punching, screaming devil. The policeman threw me from his shoulder. The side of my head cracked against the stone step. Everything went gray then black then gray again. I felt myself slipping, slipping….

Until I heard a voice cry, “Run, Mishka! Run!”

Pasha! Pasha on the steps all in a tangle with the shiny black boots that kicked him over and over and over, screaming, “Run, Mishka! Run!”

I scrambled to my feet and ran, stumbling and falling, up the stairs to the world above where the sun was just rising. I ran as fast as I could with just one Famous Basketball Player shoe. I ran until I could no longer hear the whistles and the shouts and the screams.

I ran and ran down the street and through the busy intersection and across the plaza. I was a small boy — a boy of five — running with just one shoe and a broken face and bloody fingers. I ran through an army of legs rushing this way and that, crying. And no one — not a single person — saw me.

Finally, I came to the long alley I knew so well. They would just be waking, the dogs would. The puppies would be crying for Little Mother’s milk. Patches and Lucky would stretch and lick each other’s faces, wag their tails. Rip would uncurl himself from Grandmother. Perhaps Smoke would be there.

I stumbled to the back of the building and pushed aside the weeds. They would be happy to see me. Here with the pack, I would be safe from the tall black boots and the cruel hands.

“Lucky,” I called through the opening in the bricks. “It’s me.”

I dropped into the pocket of darkness.

No warm nose pressed into my palm and searched my pockets for food. Nothing stirred. I heard a whimper. I thought, The puppies. And then I realized: The whimper had come from me.

There was nothing else in the cellar but the dark and the sound of my heartbeat.

The pack was gone.

I do not know how long I lay there in the dark. Just as in the train station it was always daytime, in the cellar it was always night.

I curled up in the mound of blankets and rags Little Mother had used as a nest for her puppies and closed my eyes. I remember the cold. I remember the pain. I remember getting up once to vomit in the corner.

But it did not matter anymore. There was no button to reunite with the red coat because there was no mother. There would never be a red coat because there would never be a mother. There was only the red, sticky smear on the floor.

And without my mother, there would never again be Mishka.

Something warm stroked my cheek, over and over.

I had been dreaming of angels, of warm, feathered wings — wings that would scoop me up and carry me away just like the Little Match Girl.

I stretched my arms out to be carried away in a blanket of feathers. Instead, my hands met thick, soft fur.

I opened my eyes and squinted into the weak light coming through the opening in the wall. A pair of yellow amber eyes stared down at me. My fingers were buried in a smoke-colored ruff.

“Smoke,” I breathed.

He licked my cheek and my ear again, then lay down next to me with a sigh. Before I could ask him about the rest of the pack, I fell asleep.

A warm, wet something pushed into my face. I pushed it away. It pushed at my face again, harder. I rolled away from the thing. “Leave me alone,” I whispered and closed my eyes.

Woof!

I drew my knees up to my chin and buried my face in my arms. “Go away and leave me alone.”

A snort. Then something tugged on the back of my sweater.

“I mean it!” I said, over my shoulder. “Go away!”

Another snort, and then I was being pulled across the dirt from my bed of rags in the dark and into the block of sunlight in the middle of the cellar floor.

“Hey,” I croaked. I squinted in the sunlight. The squinting made my face hurt. I sat up and put my hand to the side of my face. It felt big as a melon.

Smoke stood before me with a fat sausage in his mouth. He dropped it and stepped back.

“I don’t want it,” I said, and looked away.

The dog picked up the sausage and dropped it in my lap.

I looked at Smoke. He looked at me with solemn eyes. “Okay, okay,” I said. I brushed the dirt from the sausage and broke off a piece. “Just a bite to please you, then leave me alone.” I chewed the sausage on the side of my face that did not hurt. I had never, ever tasted anything so good. I closed my eyes and savored the rich taste. I ate one more bite, then another and another, until the sausage was gone.

“Thank you, Smoke,” I said, opening my eyes. But the dog was gone.

I heard a drip drip coming from somewhere in the back of the cellar. I licked my lips. How long had it been since I had had a drink of water?

I followed the sound, feeling my way through the dark. I stumbled over boxes and through cobwebs, but finally I found the source of the sound: Water dripped from an overhead pipe. I cupped my hands beneath the drip. Drips from a leaky pipe do not fill even small hands very quickly. By the time my throat was no longer dry I was exhausted. I made my way back to the patch of sunlight in the middle of the floor and slept.

In this way, time passed. I slept. Smoke woke me with food. I drank from the dripping pipe. I slept some more. The days grew colder; what little light there was in the cellar did not stay.

Sometimes I wondered about Tanya and Pasha and even Viktor. Had they escaped the beatings? Were they taken away in the vans with the flashing lights? Had Rudy come and saved them?

And I wondered even more about the rest of the pack — Lucky, Little Mother, Patches, Rip, Grandmother, and, of course, the puppies. Had Smoke abandoned them? Why had they left the cellar and where were they now? I turned these questions over and over in my mind like I used to turn the button between my fingers. My fingers ached for that button.

One day I lay in the patch of sunlight, waiting for the dog to bring food. My stomach growled and grumbled. My fingers and ears burned with cold.

Something blotted out the sunlight. I sat up and said, “Where have you been, Smoke? I’m hungry and cold.”

I waited for him to slip inside and drop something at my feet.

But this time he didn’t. He stood at the opening and peered in.

I waved my hand. “Come down here,” I said.

He barked and backed away.

“Smoke!” I called.

He barked again, farther away this time.

I crossed to the wall and called out, “Smoke! Come back here!”

Two barks, high and commanding.

> I leaned my head against my hands already gripping the edge of the opening. If I left, where would I go? How would I live?

I heard Smoke’s voice again.

With one backward look at the cellar, I pulled myself up and through the opening in the brick wall and back into the world.

The world had turned white and cold during my time in the cellar. Snow covered the trash and weeds in the alley. The sun hurt my eyes.

My toes — one set living in only a sock, the other living in one Famous Basketball Player shoe — pointed their way down the alley. I followed. I went the only way I knew to go: back to Leningradsky Station.

I watched for faces I might know and for a smoke-colored dog as I clumped my way through the frozen streets. I saw the faces of children going to school and the faces of children sleeping in doorways and in cardboard boxes. But I did not see the faces of Pasha or Tanya or Yula.

I stood at the top of the stairs leading down and down into the belly of Leningradsky Station. I clung to the cold metal of the handrail. My heart hammered so hard I thought it would burst through my chest.

Someone pushed me from behind. “Move it, kid.” I stumbled down two steps, then four, five, and then I was swept down in the current of legs and bags and carrying cases until I was at the long, gleaming cavern of the station. There stood the statue of the man on the horse. There were the sparkling glass lights that made it always daytime in the station.

I stopped before my bench over the heat vent, the place I had slept night after night after night since coming to The City, and the place where I’d lost that one piece of my mother: the shiny black button. Tears stung my eyes. “You are a stupid, stupid little boy,” I muttered.

Something fluttered beneath the bench. I dropped to my hands and knees and crawled under. Pages from my book of fairy tales were just where I’d left them. I smiled as I gathered them to me. There was the firebird soaring high above the shining city. There, on the other page, was the evil witch, Baba Yaga, with her house on chicken legs. The eyes of the Little Match Girl stared up at me, asking — what was she asking? I brought the page close to my face and whispered, “What?”

Stay

Stay A Dog's Way Home

A Dog's Way Home The Dogs of Winter

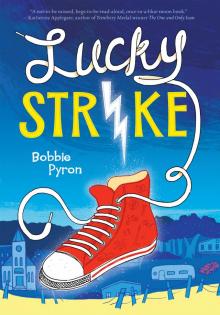

The Dogs of Winter Lucky Strike

Lucky Strike A Pup Called Trouble

A Pup Called Trouble